I’ve been experimenting with a new way to practice accuracy. I call it “Gardner’s accuracy challenge” because I heard Randy Gardner describe it during a presentation at the Kendall Betts Horn Camp back in June. I can feel it stretching and training my brain in new ways. I’ve also been reading the beginning of John Ericson’s new blog topic series, over at Horn Matters, called Accuracy Encyclopedia (part 1, part 2).

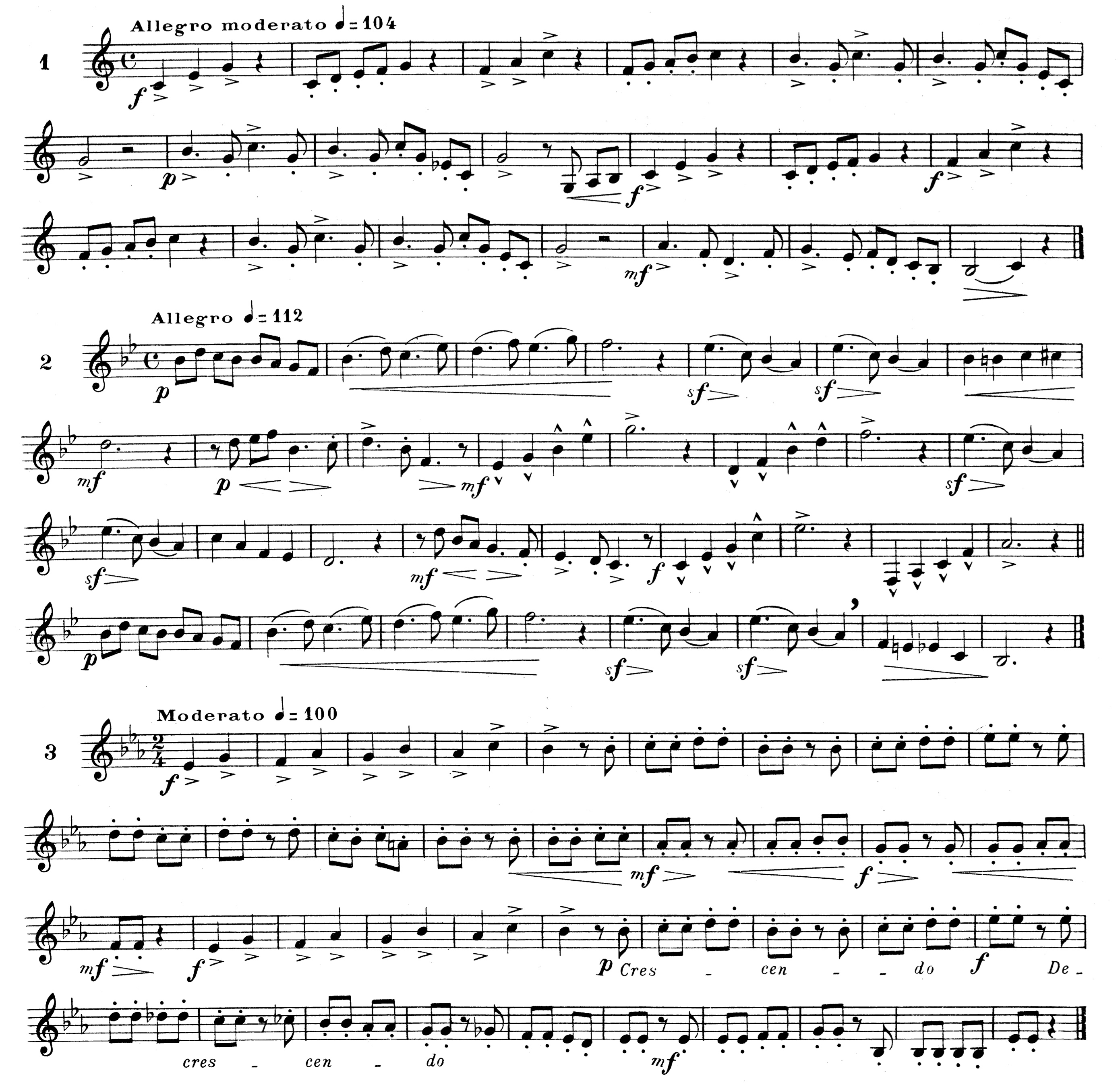

Gardner’s challenge uses Maxime-Alphonse Book 1. Starting at the beginning of the book, play etudes 1 through 3, straight through, without stopping. If any notes are missed or chipped, then come back to it the next day and try again. Keep doing that until you play all three etudes cleanly; after that, you can move on to the next three etudes in the book.

17-Sep-2023 update: I didn’t remember Randy’s explanation correctly. He says:

Progress one etude at a time.

Require yourself to perform each etude three times perfectly (including clean attacks, accurate dynamics, etc.) before moving on to a different etude. If you miss the first note of a performance, play the entire etude through before restarting. Begin the process all over if you miss the last note of the third repetition.

Following a sing-buzz-play process compounds the benefits. Sing an etude accurately and in-tune, then buzz the etude accurately and in-tune, before performing it on your horn.

This sing-buzz-play process is highly productive when addressing accuracy challenges in any repertoire.

See the “Accuracy and Intonation” chapter of Randy’s book, Good Vibrations: Masterclasses for Brass Players.

My apologies for the confusion!

Randy said he sometimes suggests this as something to try during the summer, and he warned us that it could be frustrating and require a lot of patience. He said that some of his students have needed weeks to move past the first three etudes. (I can now report that I also belong to this group!)

From 200 Études nouvelles mélodiques et progressives pour cor, book 1, by Maxime-Alphonse

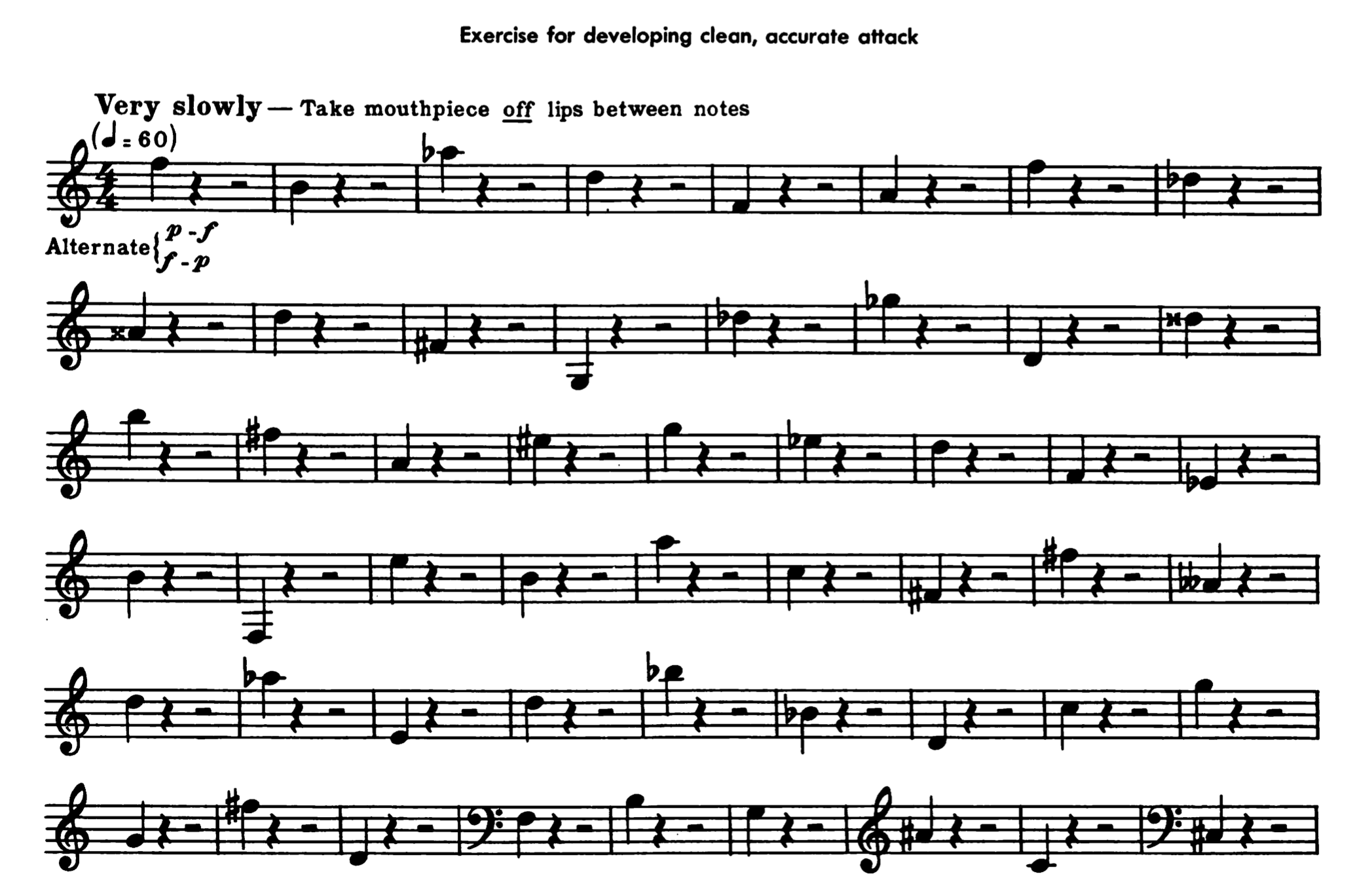

Compare that with the famous Farkas accuracy exercise.

A portion of the accuracy exercise from The Art of French Horn Playing, by Philip Farkas

Farkas says:

The notes are purposely combined in an unrelated manner so that the ear will aid as little as possible in the attacks. Of course, try to hear the notes and intervals before each attack; but particularly for the purpose of this exercise, try to “taste” each note. Every note has a distinct muscular setting, almost a “flavor” of its own.

I found the Gardner challenge to be very different from practicing the Farkas exercise. Unlike Farkas, the intervals in the etudes are straightforward and predictable. It requires a different kind of focus and flow. In a way, it needs a split-brain concentration. Part of the brain must be accurately audiating the interval for the very next note, and another part of the brain has to be looking a few beats ahead to get ready for what is coming next.

After each etude, I take a moment to mentally review the feeling of what just happened. Which notes were missed, and why? It was usually an issue of air or of hearing the interval.

John Ericson says he has been working a long time on a possible book about accuracy, and he plans to add a bunch of new material on the topic to Horn Matters in the next year. In “Adjust your thinking,” he talks about the wide variety of horn players and their reasons for missing notes. For some, they may need to “trust [themselves] more and try less hard to play perfectly.” Others may have grown too accustomed to missing a certain percentage of notes and might need to challenge themselves to reach a higher level.

“Air and Alternate Fingerings” opens with a discussion on air and timing in the breath/set/play sequence. When John says, “you can’t bottle up air as part of that [sequence] and expect to play as accurately,” I can sense my teacher, Hazel, looking over my shoulder and nodding, saying “See, I told you so!”

There’s a lot of material on accuracy already at Horn Matters. Check out the accuracy category.

John says, “there are at least 1,000 ways to miss a note.” Oh great! That means I probably have about 750 ways still left to discover.